LLM Semiotics: When Language Models Become Digital Artifacts

For a field that's so obsessed with the future of humanity, we care alarmingly little about how our LLMs will be used by our descendants.

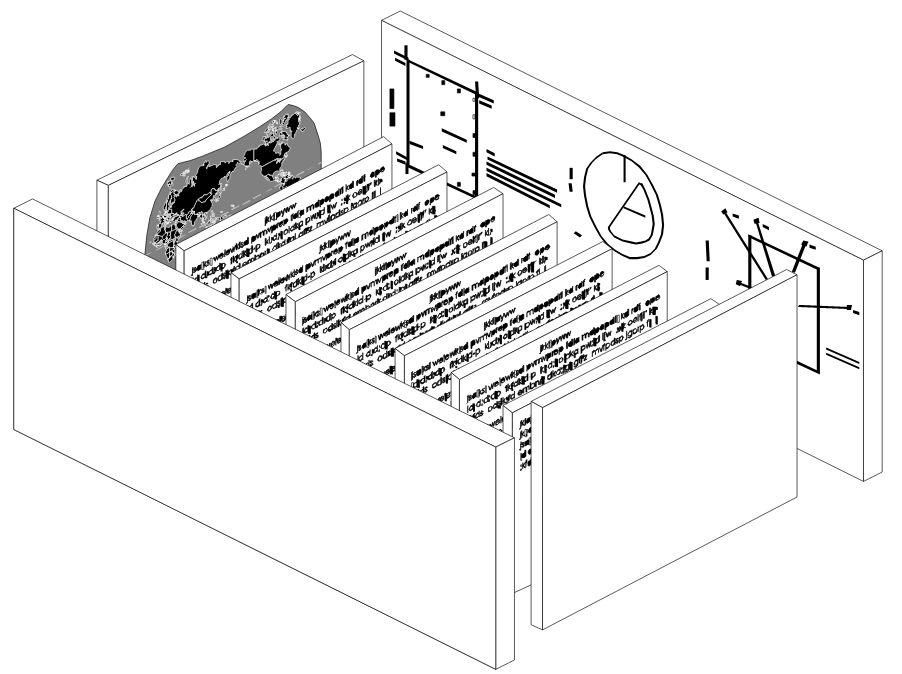

Landscape of Thorns, Sandia Report

I discovered nuclear semiotics the other day. What a crazy field.

It's one of those tiny, obscure disciplines that few people know about, but once encountered, it's unforgettable. The problem it tackles: imagine you have a bunch of nuclear waste that you need to get rid of. You've decided to bury it. The issue is that the nuclear waste is going to be nuclear for a while – at least 10,000 years. How do you tell people in the distant future to not go near it?

Your first instinct may be to say, "with words, duh." This is where it gets tricky. You can't trust languages – they evolve. The people who speak your language may migrate. It may go extinct. What about visual signs? It turns out that those aren't nearly as universal as you thought. Only a minority of people worldwide can identify the trefoil ("radioactive sign") today – surveys show that as little as 6% of the general public can correctly identify common pictograms relating to radioactive danger.[1] It's shocking, but it gives you an idea of the difficulties in creating a universally recognized symbol.

Thankfully, large language models (LLMs) aren't as lethal as enriched plutonium – and thankfully no one is trusting me with such materials – but it did get me thinking. These models will likely persist in digital form long after their creation. The assumptions may be different – we'll get to that in a second – but the same question persists: do we need to future-proof our documentation, and if so, how?

I'm a computational linguist. I barely even know what it means for something to be radioactive. I study how context is represented in language, and how it's expressed (or not) in LLMs. And in this climate, like many others, I find it difficult to not worry about how my actions will affect people around me, both in the present and future. I find myself wondering about LLMs, not as an AI, not as compressed information, but as a cultural artifact. What responsibility do we have to document these AI systems not just for current users, but for future generations who might discover and study them as some sort of snapshot into our society?

In advance: this post is a hypothetical and shouldn't necessarily be taken as some sort of call to action. At most, it's maybe a joke about the current state of science.

Nuclear Semiotics

Nuclear semiotics was born in the 80s, during the height of the cold war. As nuclear stockpiles grew and nuclear energy expanded, the question of what to do with the dangerous waste became increasingly urgent. Scientists and policymakers recognized that nuclear waste would remain hazardous far longer than any human institution could reasonably be expected to last.

The story of nuclear semiotics is deeply intertwined with the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in New Mexico, where the U.S. Department of Energy stores radioactive waste from the nation's nuclear defense program. In 1991, Sandia National Laboratories produced what remains the most comprehensive artifact in the field: "Expert Judgment on Markers to Deter Inadvertent Human Intrusion into the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant." This report, colloquially known as "the Sandia Report," brought together linguists, anthropologists, materials scientists, architects, sci-fi writers, and other experts to explore this challenge in communication.

The Sandia Report approached the problem systematically, examining how to create messages that could remain intelligible and effective for 10,000 years – roughly the span of human civilization so far. The task: design a warning system that would outlast empires, languages, and perhaps even our current understanding of science.

This is a visceral, existential challenge. It forces you to deconstruct everything you take for granted about human communication. What remains when you strip away language, cultural context, and shared knowledge? You begin to see how deeply your understanding of the world depends on cultural frameworks that could vanish entirely. Your most fundamental symbols and warnings—which seem so obviously meaningful today—appear suddenly fragile and arbitrary. It's a form of cognitive vertigo, or maybe intellectual nausea, staring into an abyss of meaning that transcends your own mortality. The weight of communicating across such vast timeframes confronts you with the impermanence of everything you consider stable and universal. How do you even begin to express the feeling this evokes?

The authors of the Sandia report clearly understood this and make no attempt to characterize the challenge as anything but an appeal to the deepest, darkest crevices of the human psyche. The following text is included as an example of what messages should be conveyed:

This place is a message... and part of a system of messages... pay attention to it!

Sending this message was important to us. We considered ourselves to be a powerful culture.

This place is not a place of honor... no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here... nothing valued is here.

What is here was dangerous and repulsive to us. This message is a warning about danger.

The danger is in a particular location... it increases towards a center... the center of danger is here... of a particular size and shape, and below us.

The danger is still present, in your time, as it was in ours.

The danger is to the body, and it can kill.

The form of the danger is an emanation of energy.

The danger is unleashed only if you substantially disturb this place physically. This place is best shunned and left uninhabited. [2]

Not ideal. But the emotional tone of this message is deliberate. The report identifies four levels at which these messages – feelings – should be conveyed:

- Rudimentary information: "Something man-made is here"

- Cautionary information: "Something man-made is here and it is dangerous"

- Basic information: Tells what, why, when, where, who, and how

- Complex information: Highly detailed written records, tables, figures, maps, and diagrams [2]

Putting existential dread aside – this approach is brilliant. The Sandia Report acknowledges that there is no way that any one signal is going to effectively convey such a message. They propose, instead, to make the whole site a message itself, designed to convey meaning through:

- A Gestalt, in which more is received than sent,

- A Systems Approach, where the various elements of the communications system are linked to each other, act as indexes to each other, are co-presented and reciprocally reinforcing, and

- Redundancy, where some elements of the system can be degraded or lost without substantial damage to the system's capacity to communicate. [2]

This effort is such a testament to systems engineering. If you read the report, you'll find all of these intricate risk analyses, simulations, and decision science applications. What makes the Sandia Report so groundbreaking isn't just its philosophical depth, but its practical approach to an almost impossible communication problem. It acknowledges that we cannot predict how humans will evolve culturally or linguistically over millennia, so instead it develops a multi-layered system designed to work across different levels of understanding.

Proposed Solutions

The Sandia Report enumerates a variety of solutions, most (if not all) relying on physical artifacts.

There's a lot of discussion about covering the geographic region in monolithic, randomly scattered concrete spikes, asphalt slabs, giant stone blocks, or other hostile architecture. These are your level one and two signs – the area contains something manmade, and is clearly you don't belong there.

The report also suggests thousands of metal plaques dispersed throughout the region, buried at varying depths, containing level II and III messages: the area is dangerous, here's what we put here, don't dig.

Near the actual location of the nuclear waste would be an information center containing level IV messages. The idea here is that the more people want to know more about the site, the closer they will try to get to the epicenter of danger. This information center would look like an open-air collection of granite slabs, engraved with critical detailed information. The report mentions designing the information center so that a "dissonant and mournful" sound is created as the wind blows through it.

All written messages would be translated into all UN written languages, as well as Navajo, the language indigenous to the WIPP's location.

Of course, this doesn't guarantee that humanity 10,000 years in the future will understand any of the written messages placed in the site. We don't even know what languages we spoke 10,000 years ago. Written language is a comparatively recent human invention. And there's a nontrivial chance we'll lose it and reinvent it again, perhaps several times, in the future.

Deciphering unknown languages is extraordinarily difficult, but not impossible, especially when given parallel corpora in other languages. The Rosetta Stone cracked Egyptian hieroglyphics by presenting identical content in three scripts. Similar breakthroughs came with Linear B, the oldest known form of Greek writing. Even with ancient writing systems like Rongorongo or Proto-Sinaitic, partial decipherment has been possible through pattern recognition and comparative analysis. This is why the WIPP's multilingual approach makes sense – if future humans can decode just one of the languages, they potentially have keys to all the others. It's a small but real chance that even after 10,000 years, some warning message might still be understood. But this assumes future civilizations will have maintained or redeveloped the intellectual tools and archaeological techniques needed for such work. This is a significant assumption, but one rooted in the persistent human drive to understand the past.

There are some other proposed solutions outside of the Sandia Report that are worth mentioning. Personal favorites of the community include "ray cats"[4] – genetically engineered cats that change color when exposed to radiation – or an atomic priesthood that codifies the message into ritual and belief. These proposals may ostensibly sound ridiculous, but reveal a crucial insight: maybe complex technical explanations are just less durable than simple cultural associations or beliefs. Why bother trying to get such a complicated message to live 10 thousand years when something simpler could suffice?

After all, embedding messages in cultural practice is a tried and true method. Jews – my family and I – are a living testament to this. How else could a cohesive social identity survive for 3000 years under constant marginalization and countless near-extinction events? The Tanakh itself is a remarkable example of information preservation - not just through written scrolls, but through oral traditions, rituals that encode historical narratives, dietary practices that reinforce group identity, and holidays that reenact foundational stories. Even without political power or territorial control for much of its history, Judaism has maintained its core knowledge with incredible precision – who we are, where we come from, what we do, and when to run – through practices embedded in daily life, familial relationships, and community structures. The message wasn't just preserved in artifacts but lived through people. Maybe the most durable warnings aren't those carved in stone but those woven into the fabric of human experience and transmitted through cultural practices that adapt while preserving essential meaning.

You can argue Judaism is a lot of things: religion, ethnicity, culture, nationality, the list goes on. But for the purposes of this article, Judaism is one of the world's oldest engineered distributed communication systems, complete with multimodal communication, redundancy, and failsafes. Judaism itself is a message. It exists simultaneously as written text, oral law, stories, ritual, communal practice, lived ethics. It's a 3000 year old feeling – a sense of being, with innumerable layers that reinforce and interpret each other. When Romans confiscated scrolls or Nazis burned books, oral tradition preserved content. When communities scattered from expulsion, portable practices maintained identity. When languages shifted, interpretation evolved while core meanings persisted. That Jews are still alive today – that I am alive and Jewish – demonstrates that the most durable preservation happens when knowledge isn't just stored but lived; embedded in practices that communities find meaningful enough to maintain across generations.

But belief is fickle, fluid, subject to interpretation. Personal belief evolves to something barely recognizable in the course of a single lifetime. Such evolution can arise from abrupt catastrophes or merely the natural course of life. We have a phrase that describe this – a Jewish person going "off the derech" (lit. "path") alludes to an increased disconnect from their faith, lifestyle, and community. It's something we all experience in the course of our lives. Just like how physical artifacts can erode over time or become culturally alienated, cultural beliefs can see a myriad of expressions diachronically, and many would become so distorted that they are no longer useful to the original purpose.

At this point, the problem becomes a nearly insurmountable tradeoff analysis. And all I can say is thank god that I'm not the one who has to make the decision.

Note: There are a ton of great video essays on Nuclear Semiotics if you'd like to learn more. Check out the citations if you want some links

LLMs as Cultural Artifacts

I've drawn a lot of bizarre comparisons in this post. Just for the record, yes, I realize how it sounded when I specifically compared LLMs to enriched plutonium. So before going further, I want to highlight the similarities, differences, and requisite assumptions that are changed.

While it would be really funny to try to convince you otherwise, no, standing within a certain proximity to a LLM will not kill you. There is nothing about PyTorch weights that are lethal.

But LLMs are still dangerous. They can be used to produce disinformation at an industrial scale. It wouldn't be impossible to destabilize an economy or government with one. Worst of all, it's alarmingly easy to convince a human that a LLM is anything more than what it is – a next word predictor. We may mythologize our own intellect, but it doesn't change the fact that we are easily suggestible animals. You could tell a human most ridiculous garbage and they would believe it. ChatGPT told you to jump off a bridge? You're one terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day away from seriously considering it. You ask an LLM to justify its reasoning? Any reason it gives you beyond "this was the most likely sequence of tokens" is practically a lie. And the best part is that it wouldn't even be lying to you – autoregressive text generation algorithms simply aren't bound by the same conversational conventions that we are (if you're curious about what I mean, look up Grice's Cooperative Principle).

But you might ask: aren't LLMs evolving at such a dizzyingly fast rate that whatever we're using now will be completely forgotten about in about a week? I think the answer depends on what you think the purpose of an LLM is.

The AI bubble is about to burst. In 2025, LLMs are largely seen by the public as technical deliverables that drive – or not, allegedly – ARR. But this understanding of "use" is myopic. Even after they are pushed into technical obsolescence, LLMs will be studied by anthropologists and historians centuries after we're gone. They will be a point of interest because LLMs are considered to mark a pivotal moment in the history of science, and we've never before created such a comprehensive account of our societies. They're literally compressions[3] of most written human knowledge into a few billion parameters.

Safety is the most obvious issue here. What if we unearthed LLMs from like 10,000 years ago or something, somehow got it working, and it came with the amount of documentation that any given software engineer today would bother to write. Could you imagine? We'd be so screwed.

Everyone knows that humans are really good at these 3 things:

1) Not following instructions, especially ones saying specifically not to do something. They get like 10,000 better at it if the instructions are being given by a scientist or qualified field expert; 2) Being delusional; 3) Making stories up.

I think this is a good time to talk about the pyramids. You know how pyramids had a bunch of inscriptions saying stuff like "DO NOT ENTER" and had a bunch of booby traps? And then we went in there anyway and it turns out there was a bunch of deadly archaic bacteria in the mummies or something? And then there there was a worldwide trend where everyone was making jokes about drinking the mystery sarcophagus juice? How many people were actually joking? As a species, we are a danger to ourselves.

And it's so funny because we'll make up these crazy stories out of nothing. There's this site Southeastern Turkey called Göbekli Tepe; it's the ruins of some millennia-old structure that was used for something. A lot of Netflix shows seem to think that "something" was fertility rituals or some other profound religious tradition. This seems plausible, there could have been some religious cult, but it also seems equally plausible that it was just an event space used for parties. Kind of like how in 10,000 years, archaeologists will unearth the ruins of Berghain, Basement, and Bassiani, and make all sorts of educated guesses about the kinds of spiritual practices the very devout attendants did there.

I don't even know if LLMs would get the chance to hurt us before we just do it ourselves. How many people have been laid off because some high level executive was told their jobs could be automated by tech that can barely tell you how many 'r's are in the word 'strawberry'? In fact, why bother speculating 10,000 years in the future when we're already convincing ourselves that LLMs are capable of rational thought who should be in any way believable?

More subtly, I think posterity should also be considered here. People in the future will use our cultural artifacts as empirical evidence to draw conclusions about themselves. LLMs may be an amalgamation of our written culture but they don't define us – and if people in the future get the wrong idea about us, they could get the wrong idea about themselves. This could manifest in so many different ways:

- Overestimating our knowledge. People in the future may think that because we created something as impressive as LLMs, surely our current understanding of knowledge is complete. They could believe that we truly understood intelligence and that our current understanding should be taken as authority, when we've merely created reasonably good prediction systems.

- Mistaking pattern recognition for sentience. People thought ELIZA was AGI in the 60s. People think whatever new OpenAI model just came out is AGI today. They'll convince themselves that anything is AGI in 10,000 years. AI's science communication is failing miserably today – granted, it's kind of difficult when the subject is something that's been present in human fantasy for thousands of years – there's no way that all of the problems that just come with being human will go away.

- Amplification of documented biases. LLMs disproportionately represent the perspectives that were most frequently documented. Future researchers might incorrectly conclude that minority viewpoints barely existed in our time, further marginalizing historically underrepresented groups. Maybe they will misinterpret our society as one monolithic culture, and decide that's what they should aspire to be (imperialism who is she????).

- Inheriting harmful values. LLMs learn to represent implicit values that are decided by the collection of documents some random ML engineer chooses during data cleaning. These values are difficult to observe, potentially harmful, and could lead to the creation of "historical values" that could be use to oppress marginalized groups. This is how religious extremist groups get created. Some Hebrew was mistranslated, and now, abortions are evil and Jews have horns.

- Social organization failures. People will try to replicate social systems that they believe worked for us, with their source of information being LLM outputs.

- False attribution of agency. If they haven't reached a point where they've made similar technology yet, there could be ethical confusion about their own relationship with technology. They could incorrectly assume that LLMs had conscious experience, or believe that we relied on LLMs more than we actually do.

- False origin story. If distant humanity finds LLMs without any other context, they could draw incorrect conclusions about their own origins. If they were this technologically advanced 10,000 years ago, maybe they created us. Maybe it'll start a new religion that thousands will die over.

All of these are dangerous and could happen if distant humans unearthed LLMs. But I also think that any of these could happen with any other technology. Thankfully, LLMs are digital and access to LLMs is probably accompanied by access to a bunch of other information. But no guarantees – maybe it'll reappear in a fossilized thumb drive.

Our understanding of ourselves and the world around us has been anything but linear. There's no guarantee that future civilization is going to be as technologically advanced as us. Cataclysmic events hit humanity all the time, but we don't even need an asteroid or ice age to regress ourselves into a dark period. LLMs may not survive – but if they did, wouldn't you appreciate a warning? As if we'd even listen to it.

Conclusion

Throughout the proposal, appeal to rational thought is consistently used as a last resort. The plans rely on images of people screaming. Mysterious giant spikes that render a piece of land inhospitable. Environments engineered to evoke fear. Is that how our society works? At a certain point, intellect becomes useless and we rely on more primitive signals for our own safety? Where's the line?

Maybe the authors of the Sandia report were overthinking it. Maybe there's no good way to shoot a message into the future and hope it's understood on the other side. A lot of pushback the project received had to do with whether we should even be making signs – maybe we should just bury the nuclear waste in the most forgettable location possible and hope for the best. Maybe I'm overthinking it too. Maybe LLMs won't be that difficult to understand without trusty Medium tutorials. Maybe it's Maybelline.

The comparison between nuclear waste and LLMs is deeply flawed. One is physically deadly, the other's danger relies on human stupidity. But both are snapshots of our civilization's capabilities and values, frozen in time for future discovery. I'd like to think we'd try to make that discovery useful.

[1] "Investigation of Radiation Safety Pictogram Recognition in Daily Life"